World Record: Nano Membrane for Future Quantum Metrology

Nanomechanical systems have now reached a level of precision and miniaturization that will allow them to be used in ultra-high-resolution atomic force microscopes in the future

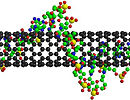

A major leap in measurement technology begins with a tiny gap of just 32 nanometers. This is the distance between a movable aluminum membrane and a fixed electrode, together forming an extremely compact parallel-plate capacitor—a new world record. This structure is intended for use in highly precise sensors, such as those required for atomic force microscopy.

Ulrich Schmid, MinHee Kwon, Daniel Platz

© TU Wien

But this world record is more than just an impressive feat of miniaturization—it is part of a broader strategy. TU Wien is developing various hardware platforms to make quantum sensing easier to use, more robust, and more versatile. In conventional optomechanical experiments, the motion of tiny mechanical structures is read out using light. However, optical setups are delicate, complex, and difficult to integrate into compact, portable systems. TU Wien therefore relies on other types of oscillations than optical [DP1] that are better suited for compact sensors.

Pushing Toward the Limits of Quantum Physics

In the record-breaking structure featuring the 32-nanometer capacitor, this role is taken over by an electrical resonant circuit. In other experiments, the TU Wien team uses purely mechanical resonators whose vibrations can be deliberately coupled to one another.

Both platforms pursue the same goal: to refine mechanical and electromechanical nanostructures to the point where they will one day enable measurements limited only by the fundamental laws of quantum physics.

Ultra-Precise Measurements Through Vibrations

When you strike a drum, its membrane vibrates. The sound it produces reveals how tightly it is tensioned. “In a similar way, the vibrations of our nanomembrane are influenced by various parameters,” explains Daniel Platz from the Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems at TU Wien, who led the project together with Ulrich Schmid. “Our aluminum membrane forms a tiny capacitor together with an electrode. Combined with an inductor, this creates a resonant circuit whose resonance is extremely sensitive to any change in the mechanical vibration.”

This coupling between membrane motion and the electrical resonant circuit makes it possible to measure extremely small vibrations. Normally, such measurements are always affected by noise—uncertainties arising from various sources. Temperature can introduce noise, and optical or electrical signals are inherently noisy because they consist of discrete particles. While optical measurement methods can in principle be very precise, the structures developed at TU Wien now achieve superior noise performance, limited only by the laws of quantum physics—without relying on optical components.

This makes the technology an ideal partner for atomic force microscopy. In an atomic force microscope, a thin tip moves just above a surface. Tiny forces between the atoms of the surface and the tip generate vibrations—measuring these vibrations yields an extremely precise image of the surface. “We replace optical measurements with measurements of the electrical resonant circuit—completely without bulky optical components,” explains Ioan Ignat, who worked on the project together with MinHee Kwon. Both are currently doctoral candidates at TU Wien.

Opening the Door to the Quantum World

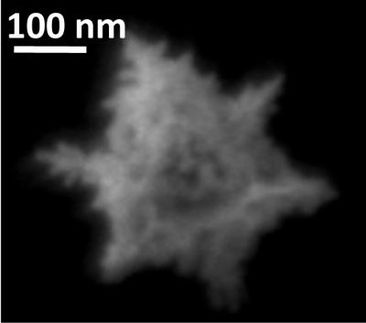

In fact, even the electrical resonant circuit is not strictly necessary. Using a different structure, the team demonstrated that purely mechanical systems integrated on a chip can also be used instead. “From the perspective of quantum theory, it makes no fundamental difference whether one works with electromagnetic oscillations or with mechanical vibrations—mathematically, both can be described in the same way,” says MinHee Kwon.

This also avoids the problem that electrical resonant circuits in quantum sensing often need to be cooled to extremely low temperatures. “Even at room temperature, the vibrations of a purely micromechanical system can be coupled over a GHz frequency range without thermal noise overwhelming the coupling effects,” says Daniel Platz. “This is remarkable, since many existing quantum sensing experiments only work near absolute zero.”

“Our results make us extremely optimistic about the future,” says Daniel Platz. “We have now shown that our nanostructures possess key properties required for manufacturing a new, reliable, and highly precise generation of quantum sensors. The door to the quantum world is now open—we are excited to see what awaits us there.”