Blood test to give insights into a person’s infection history

Researchers are investigating the immune system’s sensors

Which infections have you already come into contact with? In the future, a simple blood test may be all you need to answer that question. Researchers from Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) and Universitätsklinikum Erlangen intend to investigate the sensors the immune system uses to identify pathogens. The project is to receive approximately 1.5 million euros in funding from the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) over the next four years.

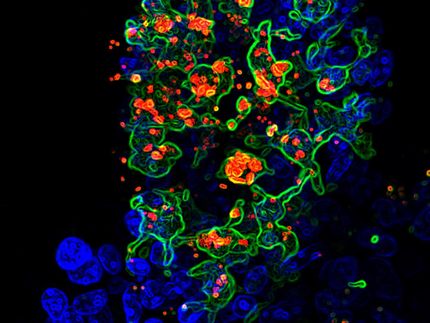

The project focuses on T-lymphocytes. These cells are involved in the immune system and act like defense troops: They are trained to recognize foreign molecules, for instance from a certain pathogen. If they find one, they raise the alarm, multiply and fight off the intruder.

However, T-cells are highly specialized: Each human being has approximately 100 million different types. And each of these types looks out for a different warning signal. Some of them become active, for instance, when they encounter a molecule from a flu virus. Others, for instance, may be stimulated by a certain protein on the surface of rubella viruses.

Receptors attach to the pathogen

These responses are triggered by sensors on the surface of the T-lymphocytes: T-cell receptors. They react to specific molecular indicators that may look very different depending on the type of the receptor. “We call these indicators antigens,” explains Prof. Dr. Kilian Schober from the Institute of Microbiology – Clinical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene (director: Prof. Dr. Christian Bogdan) at Uniklinikum Erlangen, whose research group is supported with the funding. “T-cell receptors can bind to antigens, but only if they match exactly, like a key to a lock.”

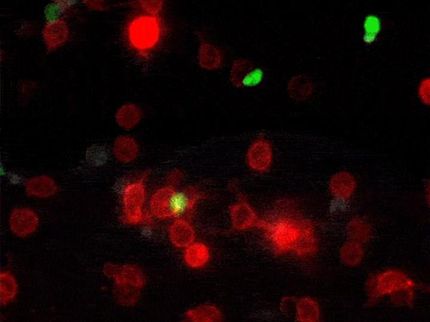

Usually, when that happens, the T-cells begin to divide rapidly. This creates a whole arsenal of identical cells, or clones. As they all have the same T-cell receptor as the mother cell, they can also recognize the relevant antigen. Most of them perish after successfully fighting the infection. However, some of them known as memory T-cells survive. They ensure that the immune system will cope better with this specific pathogen in future.

Infections leave long-lasting traces in the immune system

“Each infection leaves a trace in the immune system,” underlines Schober. “For example, if you have ever had the flu, you will have more T-cells whose receptors match the flu virus antigens than someone who has not.” Under this premise, it should be possible to determine which pathogens a person has come into contact with over their lifetime by checking which T-cells are circulating in their bloodstream. This would also provide an indication of which pathogens they can be expected to be immune to.

However, this diagnostic potential is not being fully utilized at present. The INTRA-SEQ project should change that. The acronym stands for “Infection diagnosis using T-cell receptor analysis and sequencing.” That is a fairly accurate description of the researchers’ aims: They hope to determine which receptors multiply in the case of which infections. They hope that one little pinprick will suffice to gain an overview of an individual’s entire infection history and immune status. The basic principle is similar to established serological procedures based on antibodies, although these are generally only used for one pathogen at a time.

What are the similarities between T-cell receptors in people who have had certain diseases?

It is a complex undertaking: There are major differences between T-cell receptors in different people. Furthermore, an infection does not lead to one specific T-cell clone reproducing. Instead, each pathogen has hundreds or thousands of different distinguishing features and can trigger just as many T-cells with the matching receptors to multiply. “However, exposure to certain pathogens causes many people to develop similar or even identical T-cell clones,” Schober explains. This creates a pattern, an “immunological fingerprint”, that is highly individual when it comes to the details, but that can give reproducible indications of which pathogens a person has encountered in the past.

The researchers will therefore investigate people who have been proven to have had an infection with certain pathogens over the course of their lives. Comparing the receptors on their T-cells will then allow the researchers to identify shared features specific to these particular pathogens. The researchers will use algorithms taken from the field of machine learning. “In this way, we hope to create libraries of T-cell receptors that are typical for certain diseases,” says Schober.

Collaboration between various hospitals and institutes

The researchers are concentrating in the first instance on viruses that may lead to complications in pregnancy, for instance the rubella pathogen. The aim is, for instance, to determine whether pregnant women still have sufficient immunity from a previous rubella vaccine by analyzing T-cells. “At the same time, our data will contribute towards compiling a global database of T-cell receptor sequences connected to known pathogens,” Schober explains. “In future, a single test may then be sufficient to illustrate an individual’s infection history over their their lifetime.”

These objectives can only be realized by combining the expertise of specialists from various disciplines. The INTRA-SEQ project therefore involves collaboration between the Institute of Microbiology, the Institute of Virology (Prof. Dr. Klaus Überla, Dr. Philipp Steininger), the Department of Medicine 3 – Rheumatology and Immunology (Prof. Dr. Thomas Harrer) and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Prof. Dr. Matthias Beckmann, PD Dr. Michael Schneider).