Electron spectrometer deciphers quantum mechanical effects

Electronic circuits are miniaturized to such an extent that quantum mechanical effects become noticeable. Using photoelectron spectrometers, solid-state physicists and material developers can discover more about such electron-based processes. Fraunhofer researchers have helped revolutionize this technology with a new spectrometer that works in the megahertz range.

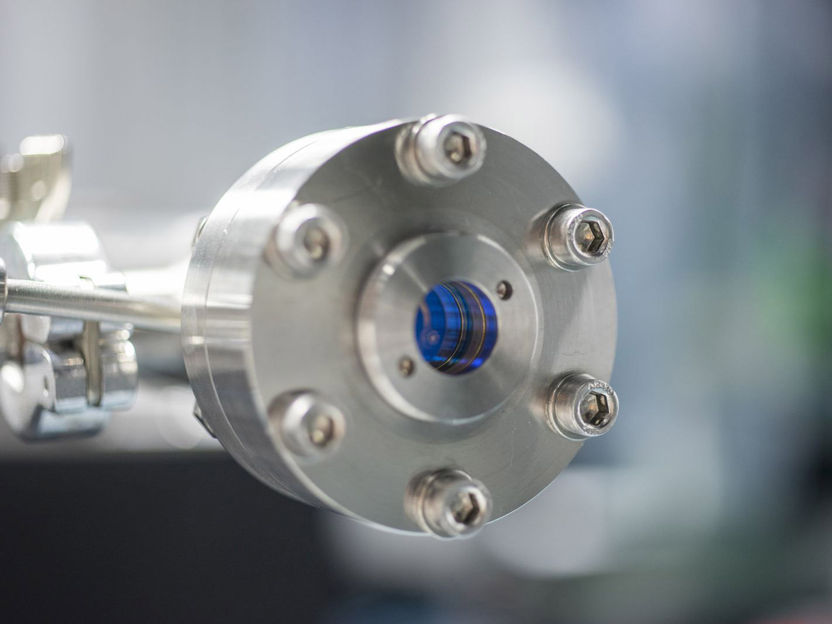

Filled with inert gas, the pressure chamber contains light-guiding hollow-core fibers. The gas and the light interact with each other. As a result, the optical spectrum widens and the pulses become shorter (30 fs).

© Fraunhofer IOF, Walter Oppel

Our vision is limited to the macroscopic world. If we look at an object, we merely see its surface. At the nanoscale, things would appear very different. This is a world of atoms, electrons and electron bands, in which the laws of quantum mechanics hold sway. Investigating these tiniest building blocks of matter more closely is a very interesting avenue for solid-state physicists and material developers – such as those who work on electronic circuits, which are so miniaturized in some cases that quantum mechanical effects become noticeable.

Photoelectron spectroscopy opens a window on atoms together with their energy states and their electrons. The principle can be described as follows: Using a laser, you shoot high-energy photons (particles of light) onto the surface of the solid-state object to be investigated – an electronic circuit, for instance. The high-energy light knocks electrons out of the atomic bond. Depending on how deep the electrons are located in the atom – or more precisely, what energy band they are in – they reach the detector at a sooner or later time. Analyzing the time it takes electrons to reach the detector, material developers can draw inferences about the energy states of the electron bands and the structure of the atomic bonds in the solid. Just like in a race, all the electrons must start at the same time – otherwise, the race cannot be analyzed. This kind of simultaneous start can be achieved only by using a pulsed laser beam. Put simply: You shoot the laser onto the surface, look at what has been released – and shoot again. Usually the lasers work in the kilohertz range, which means they emit a few thousand laser light pulses per second.

The problem is that if you set too many electrons free simultaneously with a pulse, they repel each other – making it impossible to measure them. So you turn down the power of the laser. To be able to nevertheless measure enough electrons for a reliable sample, you need to arrange for suitably long measurement times. But sometimes this is not feasible, as the samples and beam source parameters cannot be kept sufficiently stable over such a long period. Slashing measurement times from five hours to ten seconds.

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institutes for Applied Optics and Precision Engineering IOF and for Laser Technology ILT have worked together with their peers from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics to develop the world’s first photoelectron spectrometer that does not work in the kilohertz range, but at 18 megahertz. This means that several thousand times more pulses strike the surface than with conventional spectrometers. This has a dramatic effect on measurement times. “Certain measurements used to take five hours; we can now complete them in ten seconds,” says Dr. Oliver de Vries, scientist at Fraunhofer IOF.

Amplifying and shortening laser pulses

The spectrometer consists of three main components: an ultrafast laser system, an enhancement resonator and a sample chamber with the actual spectrometer itself. As the initial laser, the researchers use a phase-stable titanium-sapphire laser. They change its laser beam in the first component: by means of pre-amplifiers and amplifiers, they ramp up the power from 300 microwatts to 110 watts – a millionfold increase. In addition, they shorten the pulses. To do this, they use a trick whereby the laser beam is shot umpteen times through a solid, which widens the spectrum. If you then put these newly created frequency components of the pulse back together again – that is, if you combine all frequencies in a phase-correct manner – you shorten the pulse duration. “Although this method was already known beforehand, it was not possible until now to compress the pulse energy that we need here,” says Dr. Peter Rußbüldt, group manager at Fraunhofer ILT.

Increasing the photon energy

The pulse duration of the laser light leaving the first component is already very short. However, the energy of its photons is not yet sufficient to knock electrons out of the solid. In the second component, the researchers therefore increase the photon energy and shorten the pulse duration of the laser beams once again in a resonator. Mirrors steer the laser light around in a circle several hundred times inside the resonator. Each time the light passes the starting point again, fresh laser radiation from the first component is superimposed onto it – and this is done in such a way that the power of the two beams is added together. Bottled up in the resonator, this radiation reaches such powerful intensities that something amazing happens in a jet of gas – high-energy attosecond XUV pulses are generated with many times the frequency of the laser beam.

The researchers at Fraunhofer ILT use another trick to get the high-energy attosecond XUV pulses back out of the resonator. “We’ve developed a special mirror that not only withstands the high power, but also has a miniscule hole in the center,” explains Rußbüldt. The bundle of high-harmonic rays – as the high-energy laser beams are called – generated by the process is smaller than the other waves that are circulating. While the lower-energy light beams continue to hit the mirror and be steered around in a circle, the high-energy bundle of rays is so thin and narrow that it slips through the hole in the center of the mirror, exits the second component and is deflected into the sample compartment inside the third component.

The prototype of the photoelectron spectrometer has been completed. It is located at the Max Planck Institute in Garching, where it is used for experiments and optimized with the collaboration of Fraunhofer researchers.

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!