Learning how the pieces responsible for interpreting the human genome work

The human genome complete sequencing project in 2003 revealed the enormous instruction manual necessary to define a human being. However, there are still many unanswered questions. There are few indications on where the functional elements are found in this manual. To explain how we develop, scientists will have to decode the entire network of biological complexes that regulate development. One of the biggest challenges is to analyse the key proteins involved in the development of a human being, namely the proteins that bind to DNA. "If the genome provides the recipe to define a human being, the DNA proteins are the "chefs" that cook it", describes Herbert Auer, manager of the Functional genomics Facility at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) and co-organizer, together with Erich Grotewold, at the Ohio State University, of the Barcelona Biomed Conference, "The DNA proteome". Invited by IRB Barcelona and the BBVA Foundation, twenty-one authorities in the field of genomics presented their recent work at the "Institut d'Estudis Catalans", in Barcelona.

Thomas Gingeras, from Cold Spring Harbor, and Michael Snyder, from Yale University, both at US, explained in press conference that "we are at an exciting time in Biology. As Herbert Auer suggests we are defining the instructions encoded in the genome. For instance, we can now relate that many mutations found outside the genes are in regulatory regions for genes. This was accomplished by identifying where the regulatory networks are located".

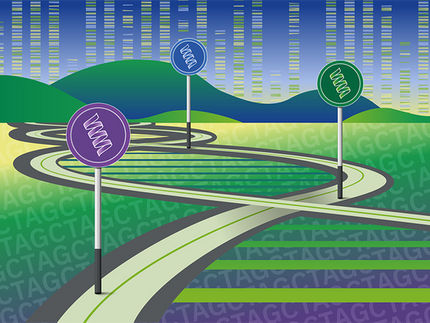

Gingeras and Snyder are both scientists involved in the ENCODE project – the consortium of the encyclopaedia of DNA elements -, the largest international study being performed today on discovering the functional elements of the human genome. In 2007, ENCODE provided the first surprising data on the elements that form our genome and on its regulation, breaking some of the classical ideas about what genes are like and how they are regulated. In addition, this project has provided a new perspective of "non-coding DNA", that is increasingly being seen as biological important but whose precise functions are still unknown.

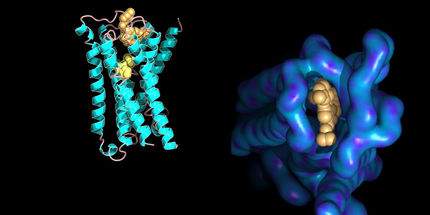

Over the last decade, researchers have revealed a very large list of DNA proteins in humans, which amounts to approximately two thousand (there are still many to be discovered). These proteins include transcription factors, chromatin histones – responsible for packaging DNA in the nucleus of the cell -, and DNA repair and protective proteins; two thousand components with key functions in the genome, being responsible for preserving, reading and executing instructions from the manual.

Michael Snyder explains that one of the greatest challenges is elucidating the combination of transcription factors that regulate sets of genes, or the so called regulator code. Thousands of transcription factors work together in distinct combinations to regulate thousands of genes. "This combination is only beginning to be elucidated. For example, distinct combinations of three proteins were found to regulate cholesterol metabolism whereas other combination regulate other cellular processes".

The main challenge for researchers is to reveal how these proteins cooperate to perform functions in healthy cells and compare this with what happens in disease and cancer tissues. "Most diseases arise as a result of the incorrect functioning of DNA proteins. For example, cancer is always an error or an accumulation of errors in DNA caused by the improper work of proteins that should protect, repair or read it". According to Thomas Gingeras, determining the interactions and functions of DNA proteins will allow us to understand how many diseases develop, particularly cancer".

To study the parallel activity of so many proteins through the genome, scientists require advanced modelling tools. These tools are associated with systems biology, which involves the "most fascinating" technology available in pioneering laboratories: Next Generation Sequencing, which was developed only three years ago.

"Using this technology, we can get detailed maps of the protein complexes that act throughout the entire genome and we can detect those elements that are required in a precise moment for the gene to be expressed", explains Auer, expert in genomic technology at IRB Barcelona. The power of Next Generation Sequencing is reflected in the following: a single laboratory could obtain in two weeks the same results as the human genome project, "when this project needed ten years of work and the collaboration of hundreds of labs worldwide", emphasizes Auer, who applies this technology at IRB Barcelona.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.