Imprisoned molecules move

Crystal cage does not hinder molecule movement

X-ray crystallography reveals the three-dimensional structure of a molecule, thus making it possible to understand how it works and potentially use this knowledge to subsequently modulate its activity, especially for therapeutic or biotechnological purposes. For the first time, a study has shown that residual movements continue to animate proteins inside a crystal and that this movement "blurs" the structures obtained via crystallography. The study stresses that the more these residual movements are restricted, the better the crystalline order. That is why molecules consisting of the most compact crystals generally make it possible to obtain structures of better quality. This research combines crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and simulation and is the result of an international cooperation involving researchers from the Institute of structural biology (ISB, CEA/CNRS/ Joseph Fourier University) in Grenoble, France, Purdue University, USA, and the Institute of Complex Systems (ICS-6: Structural Biochemistry) at Forschungszentrum Jülich in Germany.

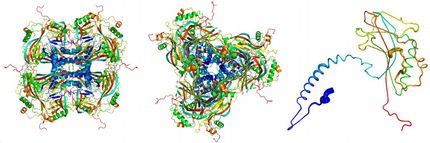

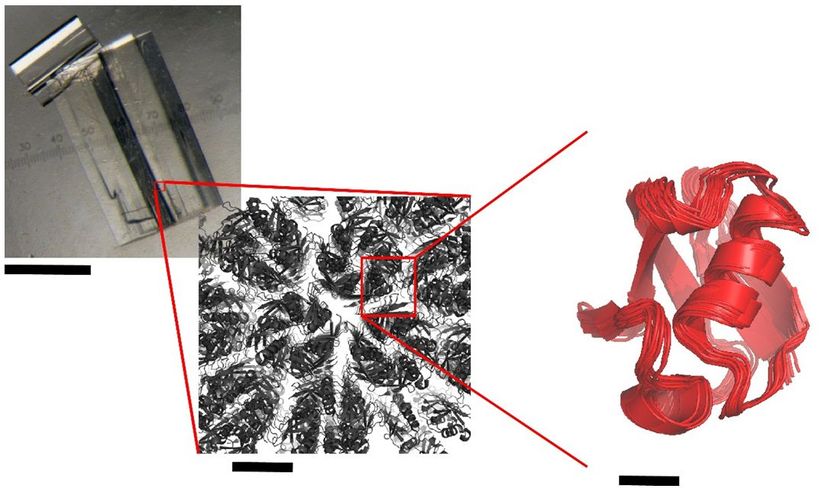

Observation of a typical protein crystal used to study molecular structures by crystallography. Left: as seen with the naked eye; in the center: model of the arrangement of proteins in a crystalline structure; Right: schematic representation of the movement of a protein by a few degrees inside a crystal, as observed through NMR spectroscopy and simulation of the molecular dynamics. Due to these movements, the protein structure that can be obtained via crystallography becomes "blurred".

Paul Schanda/CEA

X-ray crystallography is the most prolific method for determining protein structures. The quality of a crystallographic structure depends on the "degree of order" within the crystal. Proteins are generally only a few nanometres in size. Several thousand billion protein molecules must perfectly fit together in order to create a well-ordered crystalline structure in three dimensions. This stage is necessary if a structure is to be successfully obtained. Sometimes crystals, which may appear macroscopically perfect, disintegrate if subjected to X-rays, thus destroying their structure. It has been suggested that mass movements of crystalline proteins might explain this paradox, but this supposedly slow residual dynamic had never been observed directly in a crystal.

The researchers at IBS used a multi-technique approach, combining solid-state NMR spectroscopy, simulations of molecular dynamics and X-ray crystallography. Thanks to solid-state NMR, they were able to measure the dynamics of a model protein, ubiquitin, in three of its crystalline forms. Their results indicate that, even when crystallised, proteins continue to produce slight residual movements. The less compact the crystal, the more unrestrained the movements within it.

Accordingly, crystallographic data collected for three types of crystal indicate that the more compact the crystal, the better it defracts, making it easier to determine the structure of the proteins of which it consists. To reconstitute the movement of proteins in these crystalline networks, simulations of molecular dynamics were performed for each of the three crystalline forms. These simulations suggest that, within crystals, proteins revolve around each other a few degrees at microsecond speed. As shown through NMR measurements, this swinging motion" is greater the less compact the crystal.

Original publication

Peixiang Ma et al.; "Observing the overall rocking motion of a protein in a crystal"; Nature Comm.; 2015

Most read news

Original publication

Peixiang Ma et al.; "Observing the overall rocking motion of a protein in a crystal"; Nature Comm.; 2015

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.