Biologist enhances use of bioinformatic tools and achieves precision in genetic annotation

José Luis Lavín Trueba, a graduate in biology and biochemistry from the University of Salamanca (Spain) and currently collaborator in the Genetic and microbiology Research Group at the Public University of Navarre, has enhanced the use of bioinformatic tools for the identification and annotation of certain fungal and bacterial genes.

In concrete, for his PhD thesis, "Strategies for the comparative genomic study of microorganisms with various levels of pregenomic information and genic complexity", Dr Lavin used an emerging discipline: bioinformatics. By using informatics tools for studying sequences of DNA and proteins, he managed to generate databases for the genetic diversity of various organisms. José Luis Lavín's thesis has two differentiated parts which have in common the design of an enhanced technique of bioinformatic analysis that enables a greater degree of precision in the results.

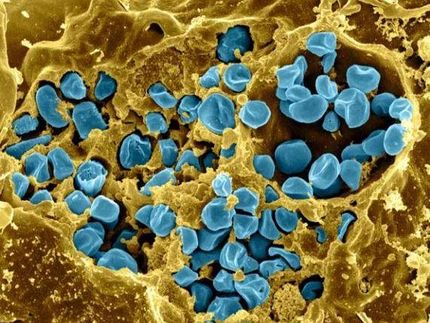

Thus, the first part of his work involved the study of bacteria, comparing genomes (the total set of genes in an organism) of pathogenic bacteria — the cause of illnesses —, both animal and vegetable. Through the comparison of genic sequences, gene candidates responsible for the infection process are detected.

As the researcher himself explains, "We used very similar bacteria and looked for differences between them. In one study, we took a plant pathogen (Pseudomonas syringae) that attacks a number of crops such as bean, soya, tomato; in another we used various genomes of the causal agent for brucellosis (the Brucella genus), given that each variety of this bacteria attacks one type of animal breed specifically. In each case what was common was recorded and we have annotated what differentiated them".

These results are available to other research teams specialising in the treatment of bacteria so that they can use these target genes and, through mutations or simply by deactivating them, it can be seen if, effectively, they are responsible for plagues and illnesses and, thereby, control these. During his stay in Denmark, in 2006, José Luis Lavín learnt the use of a new bioinformatic tool (HMM software), which he now uses in his research. The novelty, he explains, lies in that all the trials were carried out by computer. He used existing techniques but in such a way that he achieved the aim sought with the least possible percentage of error. The procedure has been considerably refined, given that, until now, the different techniques that existed were used separately and in an order that was not the correct one. Having defined parameters and a manual of correct procedure, very good results were achieved and with a minimum margin of error.

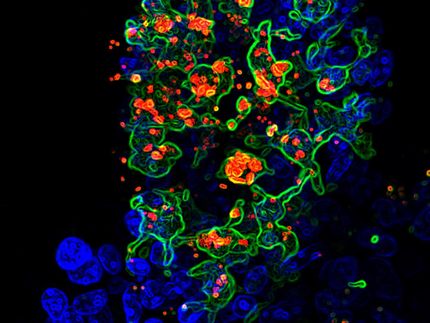

The second part of José Luis Lavín Trueba's PhD focused on certain fungal genes, known as OXPHOS genes. These, if presenting defects in the human species, may produce illnesses such as Alzheimer, Parkinson's, muscular dystrophies, etc. There are currently 27 genomes of fungi that have been sequenced and, amongst of all these what has been done is to detect what the differences are in the genes of the OXPHOS route.

They did something similar as in the first part of the research with bacteria: they used bioinformatic tools and optimised them in order to achieve the detection of OXPHOS genes in the different genomes of the fungi; they looked for a methodology that enabled them to identify these genes with the greatest possible precision. In fact, this methodology is the reference pattern for a number of international projects for the sequencing of fungi genomes in which the Public University of Navarre research team also takes part.

This unification of criteria and the procedure will enable greater precision for future researchers. The incorrect use of the tools that existed gave rise to anomalies – at times not detecting genes in a fungus when, in fact, they existed, or vice-versa.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.