Understanding nature's most striking colors

The tulip called Queen of the Night has a fitting name. Its petals are a lush, deep purple that verges on black. An iridescent shimmer dances on top of the nighttime hues, almost like moonlight glittering off regal jewels.

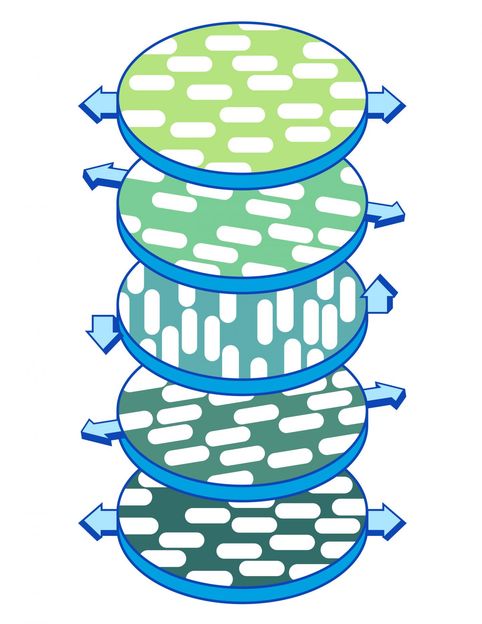

A schematic of cellulose fibers in the cholesteric phase. The fibers in a single layer align in a single direction. Travelling through multiple layers, the axis of orientation of the fibers spins in a circle.

Abigail Malate

Certain rainforest plants in Malaysian demonstrate an even more striking color feature: Their iridescent blue leaves turn green when dunked in water.

Both the tulip's rainbow sparkle and the Malaysian plants' color change are examples of structural color - an optical effect that is produced by a physical structure, instead of a chemical pigment.

Now researchers have shown how plant cellulose can self-assemble into wrinkled surfaces that give rise to effects like iridescence and color change. Their findings provide a foundation to understand structural color in nature, as well as yield insights that could guide the design of devices like optical humidity sensors.

Starting with Twisting Cellulose

Cellulose is one of the most abundant organic materials on Earth. It forms a key part of the cell wall of green plants, where the cellulose fibers are found in layers. The fibers in a single layer tend to align in a single direction. However, when you move up or down a layer the axis of orientation of the fibers can shift. If you imagined an arrow pointing in the direction of the fiber alignment, it would often spin in a circle as you moved through the layers of cellulose. This twisting pattern is called a cholesteric phase, because it was first observed while studying cholesterol molecules.

Scientists think that cellulose twists mainly to provide strength. "The fibers reinforce in the direction they are oriented," said Alejandro Rey, a chemical engineer at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. "When the orientation rotates you get multi-directional stiffness."

Rey and his colleagues, however, weren't primarily interested in cellulose's mechanical properties. Instead, they wondered if the twisting structure could produce striking optical effects, as seen in plants like iridescent tulips.

The team constructed a computational model to examine the behavior of cholesteric phase cellulose. In the model, the axis of twisting runs parallel to the surface of the cellulose. The researchers found that subsurface helices naturally caused the surface to wrinkle. The tiny ridges had a height range in the nanoscale and were spaced apart on the order of microns.

The pattern of parallel ridges resembled the microscopic pattern on the petals of the Queen of the Night tulip. The ridges split white light into its many colored components and create an iridescent sheen - a process called diffraction. The effect can also be observed when light hits the microscopic grooves in a CD.

The researchers also experimented with how the amount of water in the cellulose layers affected the optical properties. More water made the layers twist less tightly, which in turn made the ridges farther apart. How tightly the cellulose helices twist is called the pitch. The team found that a surface with spatially varying pitch was less iridescent and reflected a longer primary wavelength of light than surfaces with a constant pitch. The wavelength shift from around 460 nm to around 520 nm could explain some plants' color changing properties, Rey said.

Insights into Nature and Inspiration for New Technologies

Although proving that diffractive surfaces in nature form in the same way will require further work, the model does offer a good foundation to further explore structural color, the researchers said. They imagine the model could also guide the design of new optical devices, for example sensors that change color to indicate a change in humidity.

"The results show the optics are just as exciting as the mechanical properties," Rey said. He said scientists tend to think of the structures as biological armor, because of their reinforcing properties. "We've shown this armor can also have striking colors," he said.