Exploring the standard model of physics without the high-energy collider

Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the US, have performed sophisticated laser measurements to detect the subtle effects of one of nature's most elusive forces - the "weak interaction". Their work, which reveals the largest effect of the weak interaction ever observed in an atom, is reported in Physical Review Letters and highlighted in the on-line journal Physics.

Scientists have measured the largest effect of the "weak interaction" -- one of the four fundamental forces of nature - ever observed in an atom.

Carin Cain; image copyright American Physical Society

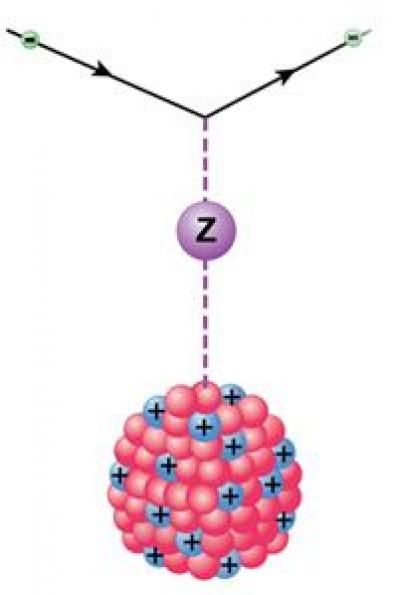

Along with gravity, electromagnetism and the strong interaction that holds protons and neutrons together in the nucleus, the weak interaction is one of the four known fundamental forces. It is the force that allows the radioactive decay of a neutron into a proton - the basis of carbon dating – to occur. However, because it acts over such a short range – about a tenth of a percent the diameter of the proton – it is almost impossible to study its effect without large, high-energy particle accelerators.

Theorists had predicted that the weak interaction between an atom's electrons and its nucleus could be quite large in Ytterbium (element 70 in the periodic table). To actually see this interaction, though, Dmitry Budker and his group at UC Berkeley had to carefully perform delicate measurements based on fundamental quantum mechanical effects and systematically eliminate other spurious signals.

The effect Budker and his colleagues see in Ytterbium is about 100 times bigger than what has been seen in Cesium, the atom in which most experiments in this field have been performed so far. The finding of such a large effect in Ytterbium poses an exciting opportunity to use tabletop atomic physics techniques as part of sensitive searches for new physics that complement ongoing efforts at the world's high-energy colliders.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.