New method for studying gene expression could improve understanding of brain disease

It takes a lot of cells to make a human brain. The organ houses not only an enormous quantity of neurons (tens of billions), but also an impressive diversity of neuron types. In recent years, scientists have been developing inventories of these cell classes--information that will be essential for understanding how the brain works. Contributing to this effort, a new study from Rockefeller scientists describes a novel methodology for characterizing neurons and their gene expression patterns with unmatched precision.

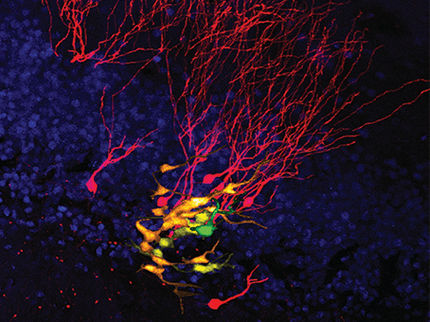

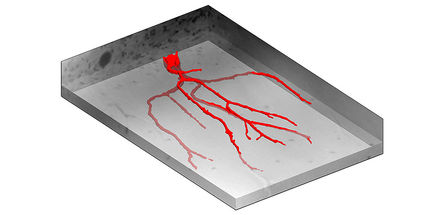

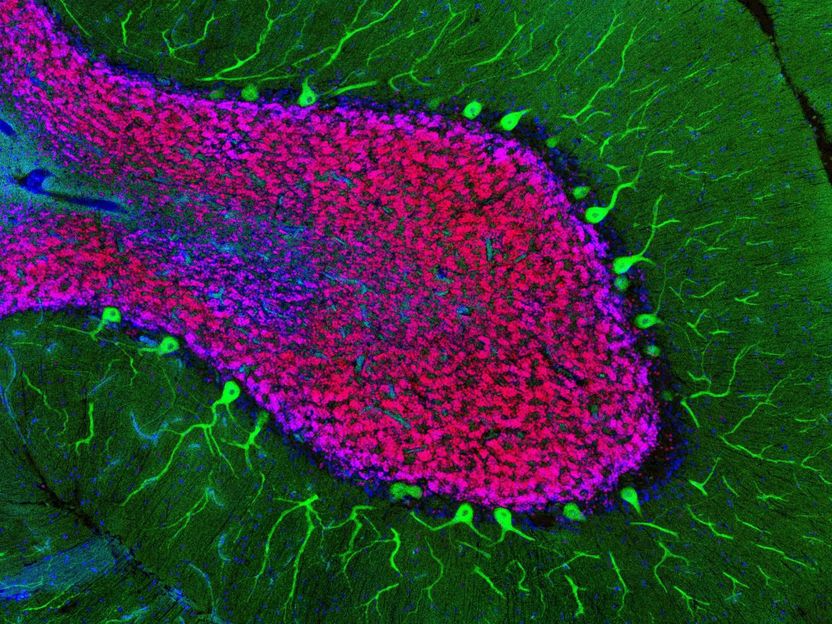

The researchers studied neurons from the cerebellum, a brain region involved in coordinating movement.

Elitsa Stoyanova and Maria V. Moya

The study suggests that even some of the most well-researched neuron types still hold secrets. The scientists show that the genes expressed by a particular cell type can vary across species, and between individuals. And, they propose, understanding these molecular distinctions could prove useful in identifying cellular abnormalities that underlie brain disease.

Gene Genie

A mouse brain is not the same as a human brain--this much is not controversial. Yet, when it comes to the cells within these nervous systems, teasing out discrepancies is not so simple. For example, granule cells are found in the cerebellar region of both mouse and human brains. And under the microscope, a granule cell looks about the same, regardless of which animal it came from.

But, it turns out, looks can be deceiving.

Nathaniel Heintz, the James and Marilyn Simons Professor, suspected that neurons from different species vary in subtle but important ways. To identify any such differences, his lab set out to determine which genes are expressed in cerebellar neurons from mouse and human brains.

Improving on established techniques, research associate Xioa Xu used cell-specific antibodies to purify nuclei from well-documented neural subtypes--Purkinje cells, granule cells, and basket cells--and to analyze which genes they expressed. To confirm these results, graduate fellow Elitsa Stoyanova used a technique called ATAC-seq, another way of determining which genes are turned on in a particular cell.

Using these approaches, the researchers found that the human neurons expressed hundreds of genes that the mouse neurons did not. Heintz attributes this disparity to evolutionary changes affecting gene regulation.

The genes that a neurons expresses determine how that cell responds to stimuli, how it is affected by disease, and how it reacts to medications. Therefore any discrepancies in gene regulation, says Heintz, could hold major implications for researchers using rodent models to study human brain disorders.

"You can't assume that when you do cross-species experiments that the results will be identical," he says. "In many cases they will, but in some cases they won't."

Changes, from brain to brain

In addition to investigating genetic differences across species, the researchers also looked for changes that might occur over the lifetime of a single individual. They found that older neurons express genes in different proportions than their younger counterparts. However, Heintz clarifies, cells don't always age at the same rate.

"When we plotted gene expression changes according to age, we observed that the cells of some individuals looked biologically older than their chronologic age," he says. "And since age is the determining factor for the onset of human degenerative disorders, it is possible that these older-seeming cells are more vulnerable to disease."

Aging, the researchers discovered, is not the only factor that can affect gene expression. In some brains, they observed distinct genetic deviations that were caused by some unknown variable--possibly a brain disorder, or possibly some other factor. More research will be required to establish what might underlie this type of change in gene expression. However, Heintz says he is encouraged by the fact that his team was able to observe these changes at all.

"This shows us that we can detect changes at the molecular level that could be important in the context of diseases affecting specific cell types in the brain," he says.