Aphids as biosensors

Do plants have some kind of nervous system? This is difficult to establish as there are no suitable measurement methods around. Plant researchers from Würzburg used aphids for this purpose – and discovered that plants respond differently to different kinds of damage.

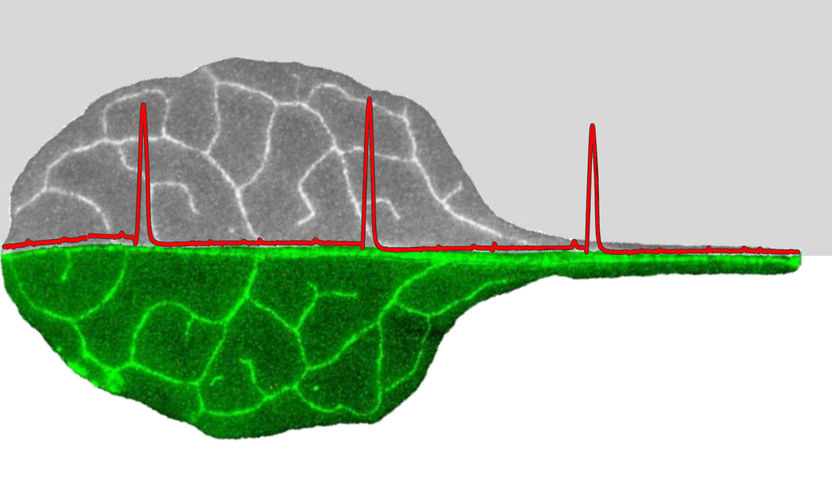

Aphids puncture the phloem vessels of plants. They can be used as biosensors for measuring electrical signals.

Jörg Fromm / Christian Wiese

Electrical signals travel alongside the sieve tube elements of plants.

Rosalia Deeken / Sönke Scherzer /Christian Wiese

When a plant is mechanically injured or exposed to cold, it will send electrical signals through its body. In both cases, the signals cover large distances of as much as ten centimetres and more. The signals travel from the areas that have been injured or exposed to cold to all other organs which then react accordingly, for example by synthesizing proteins that protect the plant against cold.

An injury triggers totally different electrical signals than a cold shock. Biophysicist Professor Rainer Hedrich of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU), Germany, and his team made this discovery using the model of thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana).

A cut injury at a leaf triggers relatively slow electrical pulses over several minutes. Exposure to cold, in contrast, causes quicker pulses about 15 seconds long. "These differences indicate that the electrical signals each have a specific meaning," Hedrich further.

Electrical signals at the sieve tubes

Could this principle be similar to that of the human nervous system? Here, electrical signals travel alongside specialized cells, bridge synapses and ultimately trigger a response in the body. Plants, however, do not have a brain, nor nerve cells or synapses. According to Hedrich, there is hence no serious scientific evidence to attribute intelligence to plants and proclaim a "plant neurobiology".

Nevertheless, many researchers today are convinced that plants also use electrical signals to exchange information between the organs of their body. Hedrich's work on the Venus flytrap has even demonstrated that the carnivorous plant is capable of counting the electrical signals sent and make decisions based on this.

Such signals can be measured in the sieve tube elements which form a system of interconnected cells that pervades the entire plant like a vascular system and usually transports sugar and other substances.

Measuring signals difficult previously

Are the sieve tubes the "green power cable" or even some kind of "nervous system of the plant? This assessment is controversial – due to a methodical issue among others: So far, scientists have not had the proper tools to measure the transmission of electrical signals in plants over longer distances.

Rainer Hedrich, Vicenta Salvador-Recatalà and Ingo Dreyer have now developed an elegant solution to this problem which they publish in the science magazine “Trends in Plant Science”: The plant scientists used aphids as biosensors. They enhanced a method that has been known since 1964 which involves an electric circuit being generated between the aphid and the plant.

Aphids allowed to suck for the benefit of research

How that works? Aphids puncture the phloem vessels of plants and suck the sugary sap. If a fine wire is glued to their body and connected to an electrode sitting in the earth of a potted plant, an electric circuit is created between aphid and plant. It allows measuring how the electrical signals propagate in the sieve tubes.

This method will now be used to answer a number of questions. How and where are the signals created? What kind of information do they carry? Where are they registered and what reactions do they trigger? So there is still plenty of work for the Würzburg scientists to do – as well as for the plant lice that puncture and suck in the name of science.