Using Gene Scissors to Detect Diseases

Sensor prototype can rapidly, precisely, and cost-effectively measure molecular signals for cancer

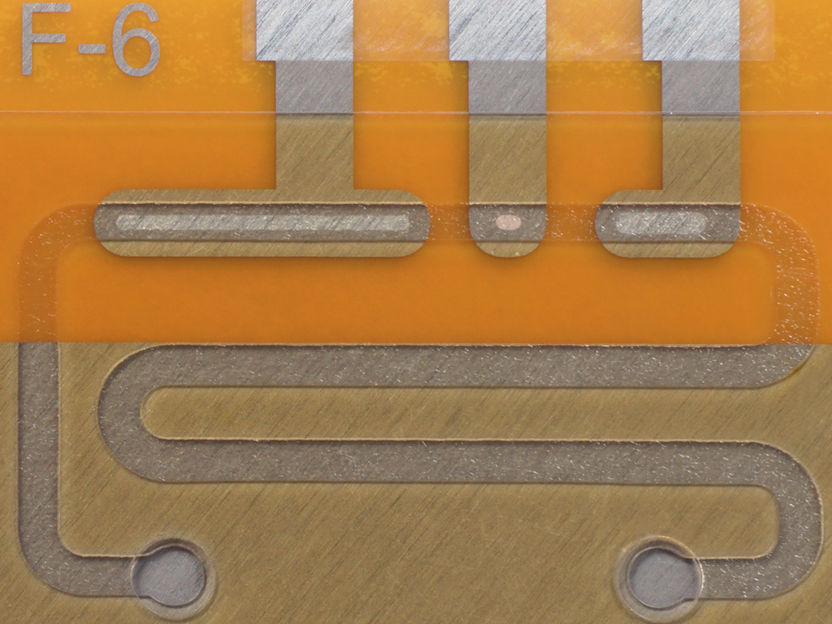

The CRISPR/Cas technology can do more than alter genes. A research team at the University of Freiburg is using what are known as gene scissors – which scientists can use to edit genetic material – in order to better diagnose diseases such as cancer. In a study, the researchers introduce a microfluidic chip which recognizes small fragments of RNA, indicating a specific type of cancer more rapidly and precisely than the techniques available up to now. The results are recently published in the scientific journal "Advanced Materials." They also tested the CRISPR biosensor on blood samples taken from four children who had been diagnosed with brain tumors. "Our electrochemical biosensor is five to ten times more sensitive than other applications which use CRISPR/Cas for RNA analysis," explains Freiburg microsystems engineer Dr. Can Dincer. He is leading the research team together with biologist Prof. Dr. Wilfried Weber, of the University of Freiburg. "We're doing pioneering work in Germany and Europe for this new application of gene scissors," Dincer emphasizes.

In a study, researchers at the University of Freiburg introduce the first electrochemical CRISPR biosensor that is to help improve the diagnosis of diseases such as cancer.

Richard Bruch

Short molecules known as microRNA (miRNA) are coded in the genome, but unlike other RNA sequences, they are not translated into proteins. In some diseases, such as cancer or the neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer's, increased levels of miRNA can be detected in the blood. Doctors are already using miRNAs as a biomarker for certain types of cancer. Only the detection of a multitude of such signaling molecules allows an appropriate diagnosis. The researchers are now working on a version of the biosensor that recognizes up to eight different RNA markers simultaneously.

The CRISPR biosensor works as follows: A drop of serum is mixed with reaction solution and dropped onto the sensor. If it contains the target RNA, this molecule binds with a protein complex in the solution and activates the gene scissors – in a way similar to a key opening a door lock. Thus activated, the CRISPR protein cuts off, or cleaves, the reporter RNAs that are attached to signaling molecules, generating an electrical current. The cleavage results in a reduction of the current signals which can be measured electrochemically and indicates if the miRNA that is being sought is present in the sample. "What's special about our system is that it works without the replication of miRNA, because in that case, specialized devices and chemicals would be required. That makes our system low-cost and considerably faster than other techniques or methods," explains Dincer. He is working on new sensor technologies at the Freiburg Center for Interactive Materials and Bioinspired Technologies (FIT) and together with Prof. Dr. Gerald Urban at the Department of Microsystems Engineering (IMTEK).

Weber, a professor of synthetic biology at the cluster of excellence CIBSS – the Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies of the University of Freiburg – emphasizes how important the interdisciplinary environment at CIBSS is for such a development: "The biologists at Freiburg work together on these technologies with their colleagues from the engineering and materials sciences. That opens new, exciting routes to solutions." The researchers are aiming to further develop the system in about five to ten years to become the first rapid test for diseases with established microRNA markers that can be used right at the doctor's office. "The laboratory equipment must nevertheless become easier to handle," says Weber.

Original publication

Most read news

Original publication

Richard Bruch, Julia Baaske, Claire Chatelle, Mailin Meirich, Sibylle Madlener, Wilfried Weber, Can Dincer, Gerald A. Urban; "CRISPR/Cas13a powered electrochemical microfluidic biosensor for nucleic acid amplification-free miRNA diagnostics"; Adv. Mater.; 2019

Organizations

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.