New sensor detects rare metals used in smartphones

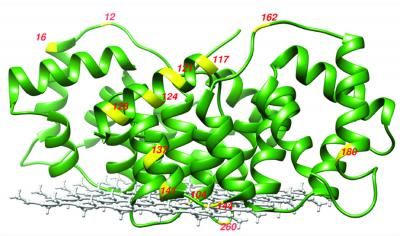

A more efficient and cost-effective way to detect lanthanides, the rare earth metals used in smartphones and other technologies, could be possible with a new protein-based sensor that changes its fluorescence when it binds to these metals. A team of researchers from Penn State developed the sensor from a protein they recently described and subsequently used it to explore the biology of bacteria that use lanthanides. A study describing the sensor appears in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

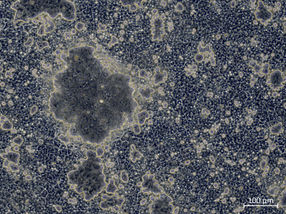

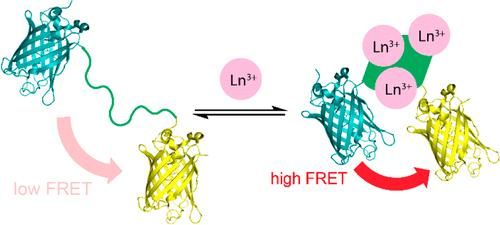

A new sensor changes its fluorescence when it binds to lanthanides (Ln), rare earth metals used in smartphones and other technologies, potentially providing a more efficient and cost-effective way to detect these elusive metals.

Cotruvo Lab, Penn State

"Lanthanides are used in a variety of current technologies, including the screens and electronics of smartphones, batteries of electric cars, satellites, and lasers," said Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., assistant professor and Louis Martarano Career Development Professor of Chemistry at Penn State and senior author of the study. "These elements are called rare earths, and they include chemical elements of atomic weight 57 to 71 on the periodic table. Rare earths are challenging and expensive to extract from the environment or from industrial samples, like waste water from mines or coal waste products. We developed a protein-based sensor that can detect tiny amounts of lanthanides in a sample, letting us know if it's worth investing resources to extract these important metals."

The research team reengineered a fluorescent sensor used to detect calcium, substituting the part of the sensor that binds to calcium with a protein they recently discovered that is several million times better at binding to lanthanides than other metals. The protein undergoes a shape change when it binds to lanthanides, which is key for the sensor's fluorescence to "turn on."

"The gold standard for detecting each element that is present in a sample is a mass spectrometry technique called ICP-MS," said Cotruvo. "This technique is very sensitive, but it requires specialized instrumentation that most labs don't have, and it's not cheap. The protein-based sensor that we developed allows us to detect the total amount of lanthanides in a sample. It doesn't identify each individual element, but it can be done rapidly and inexpensively at the location of sampling."

The research team also used the sensor to investigate the biology of a type of bacteria that uses lanthanides--the bacteria from which the lanthanide-binding protein was originally discovered. Earlier studies had detected lanthanides in the bacteria's periplasm--a space between membranes near the outside of the cell--but, using the sensor, the team also detected lanthanides in the bacterium's cytosol--the fluid that fills the cell.

"We found that the lightest of the lanthanides--lanthanum through neodymium on the periodic table--get into the cytosol, but the heavier ones don't," said Cotruvo. "We're still trying to understand exactly how and why that is, but this tells us that there are proteins in the cytosol that handle lanthanides, which we didn't know before. Understanding what is behind this high uptake selectivity could also be useful in developing new methods to separate one lanthanide from another, which is currently a very difficult problem."

The team also determined that the bacteria takes in lanthanides much like many bacteria take in iron; they secrete small molecules that tightly bind to the metal, and the entire complex is taken into the cell. This reveals that there are small molecules that likely bind to lanthanides even more tightly than the highly selective sensor.

"We hope to further study these small molecules and any proteins in the cytosol, which could end up being better at binding to lanthanides than the protein we used in the sensor," said Cotruvo. "Investigating how each of these bind and interact with lanthanides may give us inspiration for how to replicate these processes when collecting lanthanides for use in current technologies."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

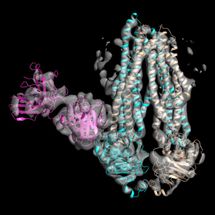

Frozen noble gas in the accelerator

Discovery of world’s oldest DNA breaks record by one million years - Two-million-year-old DNA has been identified for the first time - opening a ‘game-changing’ new chapter in the history of evolution

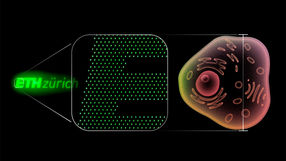

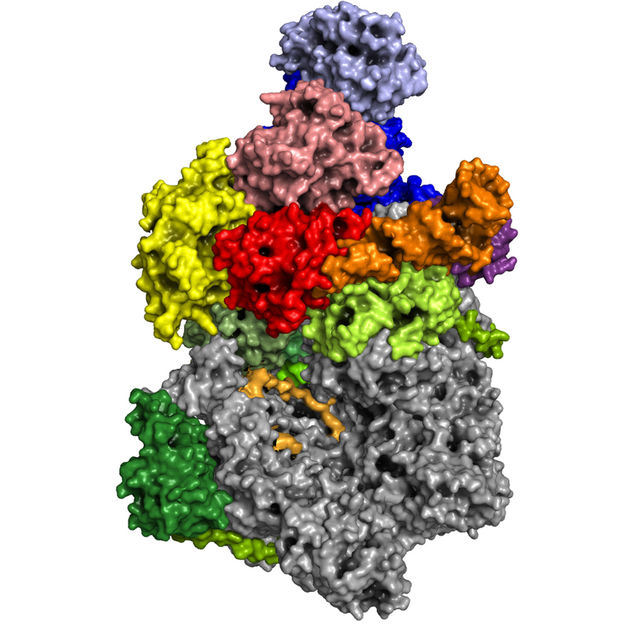

Virus multiplication in 3D

BAM develops certified PFAS reference material made from used outdoor clothing - On the way to a circular economy

Catalytic activity of individual cobalt oxide nanoparticles determined - Using a robotic arm

Exposing what’s in tattoo ink - Ingredient lists often aren’t accurate

Andor Technology plc acquires Photonic Instruments Inc.

Applied Biosystems, Roche Molecular Systems, Bio-Rad, and MJ Research Reach Settlement Agreement Regarding Thermal Cyclers