How a genetic mutation can interfere with the powerhouses of cells

A new disease mechanism in the mitochondria

Dr. Nora Vögtle, head of an Emmy Noether junior research group at the Institute of biochemistry and molecular medicine of the University of Freiburg, together with her team and in cooperation with paediatricians from Europe, Australia and the USA, has identified the molecular consequences of a previously undefined genetic mutation. This mutation interferes with the functioning of the mitochondria, known as the powerhouses of cells. It usually occurs following what would normally be a harmless infection in early childhood, leading to a severe disease and subsequently to the brain no longer being able to maintain control of key bodily functions, including motor functions.

Mitochondria are organelles that occur in higher cells and perform a variety of functions. They are best known for converting the energy stored in food into energy which can be used for cellular biochemical reactions. However they are also responsible for the production of many metabolic products and cofactors that are needed for the functioning of many enzymes. So, if something goes wrong with them, diseases can occur. Defective mitochondria lead above all to diseases of tissues and organs that demand high levels of energy. Therefore they often affect the nervous system, the heart or the skeletal muscles.

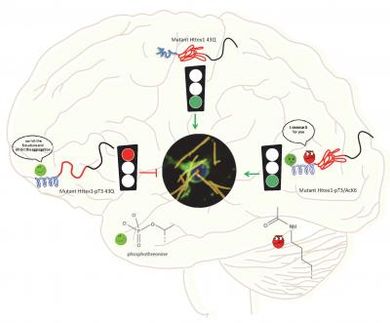

Genetic analysis of the genome of affected patients and their families from three different continents showed that a specific gene was always changed by an inherited mutation. This gene supplies the blueprint for a protein that is needed in the mitochondria. Here, this protein removes signal attachments, known as presequences, which are needed to import most of the mitochondrial proteins from the cell fluid. Therefore, it is termed as Mitochondrial Presequence Protease (MPP).

In her work at the interface of fundamental research and medicine, Vögtle and her team showed that the genetic change in the MPP gene leads to a protein with impaired functioning. It is no longer able to cleave the presequences efficiently, resulting in accumulation of immature proteins in the mitochondria. This can lead to interference with many mitochondrial functions. For parts of her study, Vögtle used baker’s yeast as a model organism. In the yeast MPP, which is related to the human gene, her team introduced the same disease-causing mutations and studied the resulting consequences on the work processes in the mitochondria.

“Sadly we have not yet been able to save any of the sick children with our findings,” says Vögtle, adding, “However without this fundamental explanation of pathological mechanisms no therapeutic approaches could be developed. We hope that our work will lead to the development of effective therapies in the long term.”

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.