LLNL researchers create tool to monitor nuclear reactors

International inspectors may have a new tool in the form of an antineutrino detector, that could help them peer inside a working nuclear reactor. A Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory-Sandia National Laboratories' team recently demonstrated that the operational status and thermal power of reactors can be quickly and precisely monitored over hour-to month-time scales, using a cubic-meter-scale antineutrino detector.

The detector could be used to determine the operational amount of plutonium or uranium necessary to run the reactor and place a direct constraint on the amount of fissile material the reactor creates throughout its lifecycle.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Adam Bernstein, leader of the Advanced Detectors Group at LLNL, is the project's principle investigator. He works on the detector development project with colleagues Nathaniel Bowden, Steven Dazeley and Robert Svoboda at LLNL; David Reyna, Jim Lund and Lorraine Sadler from Sandia National Laboratories' California branch in Livermore, and Professor Todd Palmer and graduate student Alex Misner at Oregon State University,

Antineutrinos are elusive neutral particles produced in nuclear decay. They interact with other matter only through gravitational and weak forces, which makes them very difficult to detect. However, the number of antineutrinos emitted by nuclear reactors is so large that a cubic-meter scale detector suffices to record them by the hundreds or thousands per day. As the team has demonstrated, this new detector makes practical monitoring devices for nonproliferation applications possible.

It is a long-recognized and fundamental dilemma of the nuclear age that nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons use very similar fuels. The fuels are generically known as fissile material - principally uranium and plutonium, either of which elements, in appropriate isotopic mixtures, can be used to build a nuclear device. Reactors consume uranium and produce plutonium, typically over periods of a year or so. Bombs consume either or both materials, in a few microseconds.

According to the National Academy of Engineering, nearly 2 million kilograms of highly-enriched uranium (90 percent or greater U-235) and plutonium have already been produced and exist in the world today - some from military and some from civil production. While these fuels can be and are used to produce electric power with incredible efficiency, it takes less than 10 kilograms of plutonium, or a few tens of kilograms of highly-enriched uranium, to build a bomb. There lies the nonproliferation problem.

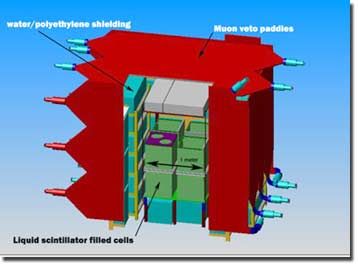

Because reactors consume uranium and are the source of all the world's plutonium, they are a critical nuclear fuel cycle element within the jurisdiction of the International Atomic Energy Agency's (IAEA) Safeguard Regime. The regime was put in place by international treaty (the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty) to detect the diversion of fissile materials from civil nuclear fuel cycle facilities into weapons programs. Part of the nonproliferation program involves comparing the actual operations of a reactor - specifically its changing plutonium and uranium inventories - with operator declarations of what the reactor is expected to produce during its normal operations. Liquid Scintillator A view into the heart of the Reactor Monitoring Antineutrino Detector: stainless steel containers hold roughly 2/3 of a ton of liquid scintillator that is sensitive to the relatively rare antineutrino interactions. The liquid scintillator is surrounded by a water shield to attenuate natural radioactive backgrounds.

That's where the new detector comes in. It provides a direct measurement of the operational status (on/off) of the reactor, measures the reactor thermal power and places a direct constraint on the fissile inventory of the reactor throughout its lifecycle. All three parameters are derived directly from the antineutrino rate, measured nonintrusively and continuously by the detector. The data can be acquired directly by the safeguards agency (for example, the IAEA) without any intervention or support from the reactor operator. The detector is located on the reactor site in an out-of-the-way location tens of meters from the core, and outside the containment dome.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.