New research paves the way for nano-movies of biomolecules

Scientists use X-ray laser as ultra slow-motion camera

An international team, including scientists from DESY, has caught a light sensitive biomolecule at work with an X-ray laser. The study proves that X-ray lasers can capture the fast dynamics of biomolecules in ultra slow-motion, as the scientists led by Prof. Marius Schmidt from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee write in the journal Science. "Our study paves the way for movies from the nano world with atomic spatial resolution and ultrafast temporal resolution", says Schmidt.

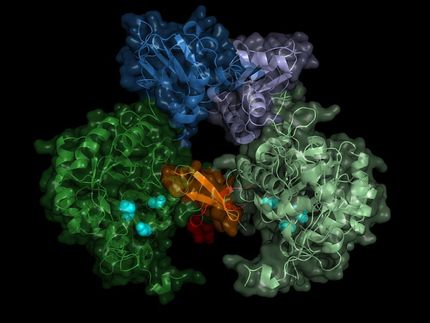

The researchers used the photoactive yellow protein (PYP) as a model system. PYP is a receptor for blue light that is part of the photosynthetic machinery in certain bacteria. When it catches a blue photon, it cycles through various intermediate structures as it harvests the energy of the photon, before it returns to its initial state. Most steps of this PYP photocycle have been well studied, making it an excellent candidate for validating a new method.

For their ultra-fast snapshots of the PYP dynamics, the scientists first produced tiny crystals of PYP molecules, most measuring less than 0.01 millimetres across. These microcrystals were sprayed into the focus of the world's most powerful X-ray laser, LCLS at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the US, as their photocycle was kicked off with a meticulously synchronised blue laser pulse. Thanks to the incredibly short and intense X-ray flashes of the LCLS, the researchers could watch how PYP changes its shape at different time steps in the photocycle, by taking snapshot X-ray diffraction patterns.

With a resolution of 0.16 nanometres, these are the most detailed images of a biomolecule ever made with an X-ray laser. A nanometre is a millionth of a millimetre. The diameter of the smallest atom, hydrogen, is about 0.1 nanometres.

Beyond reproducing known aspects of the PYP photocycle, thereby validating the new method, this investigation revealed much finer details. Also, thanks to the high temporal resolution, the X-ray laser could, in principle, study steps in the cycle that are shorter than 1 picosecond (a picosecond is a trillionth of a second) - too fast to be caught with previous techniques. The ultrafast snapshots can be assembled into a movie, showing the dynamics in ultra slow-motion.

"This is a real breakthrough", emphasises co-author Prof. Henry Chapman from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science at DESY, who is also a member of the Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging. "Our study is opening the door for time resolved studies of dynamic processes with atomic resolution."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.