Filming antibiotic resistance in Slow-Motion

X-ray laser European XFEL captures rapid reaction of bacterial enzyme

Using the X-ray laser European XFEL an international team of researchers, including scientists from DESY, has successfully filmed a reaction step that is important for the development of antibiotic resistance. The molecular film captures the very rapid reaction of the enzyme beta-lactamase from tuberculosis bacteria with the cephalosporin antibiotic ceftriaxone in slow motion. The team reports the results in IUCrJ, the journal of the International Union of Crystallography.

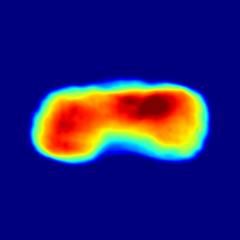

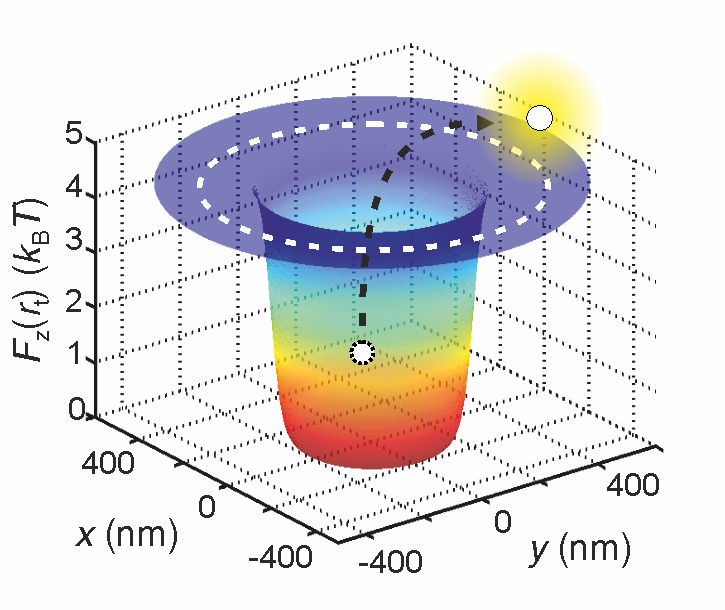

Antibiotic resistance occurs, in part, when bacteria acquire the ability to inactivate the antibiotics used against them. Many resistant bacteria produce the enzyme beta-lactamase. This enzyme can render the most commonly used beta-lactam antibiotics ineffective. The team, led by Marius Schmidt of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, have now studied the first step of this inactivation at the European XFEL, observing how the antibiotic binds to the beta-lactamase from resistant tuberculosis bacteria within milliseconds (thousandths of a second).

The researchers also investigated how the enzyme inhibitor sulbactam reacts with the bacterial enzyme. Sulbactam, administered at the same time as the antibiotics, binds to the bacterial beta-lactamase, thereby blocking it. As a result the enzyme is unable to inactivate the antibiotics whose effectiveness is restored this way.

Up to now, crystals are a requirement to study biomolecules using X-rays. Such crystals are made up of millions of individual enzyme molecules that are formed into a regular arrangement in three dimensions. If the crystals are big enough then bright X-ray diffraction patterns can be measured, which are used to reveal the spatial structure of the individual molecules and compounds in the crystal.

“We wish to make the X-ray measurements at specific times after the enzyme molecules in the crystals are brought in contact with the antibiotic,” explains DESY co-author Henry Chapman from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science CFEL. “However, when crystals are big enough for good X-ray measurements it can take several seconds for the antibiotic solution to diffuse through the crystal, smearing out the view of molecular changes that occur at faster timescales.” It was only with the advent of the X-ray free-electron lasers or XFELs, using intense pulsed beams that enable exposures that are thousands of times greater than could be tolerated before, that small enough crystals could be used. “Then, diffusion is quicker than the actual reaction so that details of the reaction can be observed,” says Chapman, who is also a member of the Cluster of Excellence CUI: Advanced Imaging of Matter at the University of Hamburg and partner institutions.

The special mix-and-inject method used in the study requires custom-made injectors, which were provided by the group of Lois Pollack from Cornell University for use at the European XFEL. The method enables atomically accurate slow-motion imaging of fast biological processes in enzymes and other biomolecules.

“Enzymes such as beta-lactamase are of great importance for medicine,” explains Schmidt. “X-ray lasers like the European XFEL now make it possible to study much smaller crystals than in the past. Our experiment, together with previous results, has shown how X-ray lasers can be used as an important tool for biological research in the future,” he adds.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the analytics and lab tech industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

The first precise measurement of a single molecule's effective charge - Discovery could pave the way to new diagnostic tools

‘Hypermutators’ Drive Pathogenic Fungi to Evolve More Rapidly