Imaging techniques set new standard for super-resolution in live cells

Scientists can now watch dynamic biological processes with unprecedented clarity in living cells using new imaging techniques developed by researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus. The new methods dramatically improve on the spatial resolution provided by structured illumination microscopy, one of the best imaging methods for seeing inside living cells.

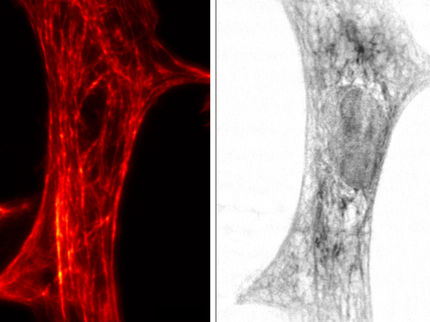

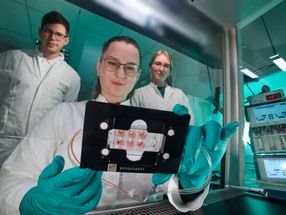

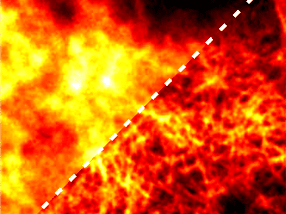

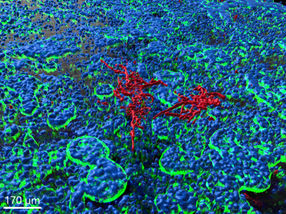

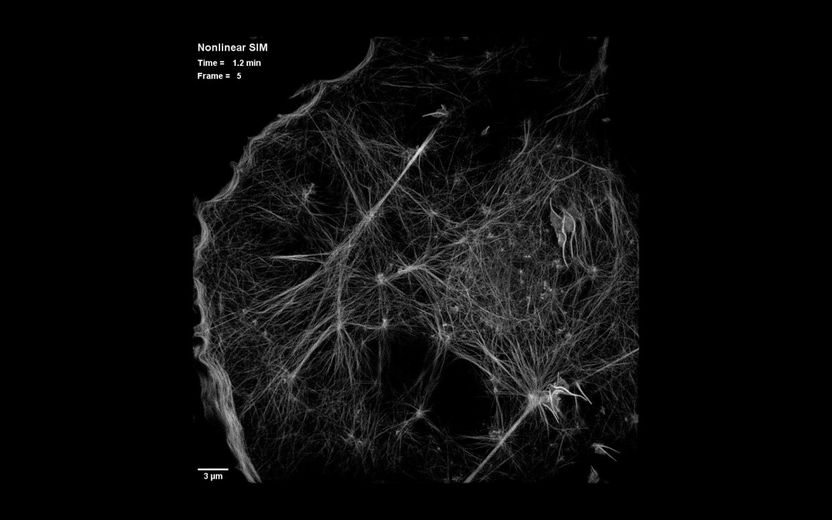

This is a still image from video showing dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton over 40 time points at 15-second intervals as seen by patterned activation nonlinear structured illumination microscopy (SIM), in a COS-7 cell at 37°C expressing Skylan-NS-Lifeact

Betzig Lab, HHMI/Janelia Research Campus

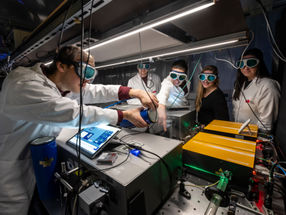

Janelia group leader Eric Betzig, postdoctoral fellow Dong Li and their colleagues have added the two new technologies to the set of tools available for super-resolution imaging. Super-resolution optical microscopy produces images whose spatial resolution surpasses a theoretical limit imposed by the wavelength of light, offering extraordinary visual detail of structures inside cells. But until now, super-resolution methods have been impractical for use in imaging living cells.

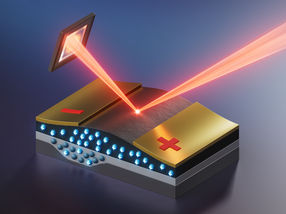

In traditional SIM, the sample under the lens is observed while it is illuminated by a pattern of light. Several different light patterns are applied, and the resulting moiré patterns are captured from several angles each time by a digital camera. Computer software then extracts the information in the moiré images and translates it into a three-dimensional, high-resolution reconstruction. The final reconstruction has twice the spatial resolution that can be obtained with traditional light microscopy.

Betzig was one of three scientists awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy. He says SIM has not received as much attention as other super-resolution methods largely because those other methods offer more dramatic gains in spatial resolution. But he notes that SIM has always offered two advantages over alternative super-resolution methods, including photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM), which he developed in 2006 with Janelia colleague Harald Hess.

Both PALM and stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, the other super-resolution technique recognized with the 2014 Nobel Prize, illuminate samples with so much light that fluorescently labeled proteins fade and the sample is quickly damaged, making prolonged imaging impossible. SIM, however, is different. "I fell in love with SIM because of its speed and the fact that it took so much less light than the other methods," Betzig says.

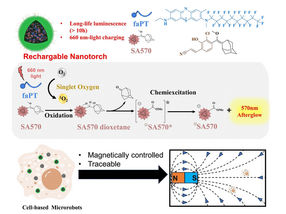

Saturated depletion enhances the resolution of SIM images by taking advantage of fluorescent protein labels that can be switched on and off with light. To generate an image, all of the fluorescent labels in a protein are switched on, then a wave of light is used to deactivate most of them. After exposure to the deactivating light, only molecules at the darkest regions of the light wave continue to fluoresce. These provide higher frequency information and sharpen the resulting image. An image is captured and the cycle is repeated 25 times or more to generate data for the final image. The principle is very similar to the way super-resolution in achieved in STED or a related method called RESOLFT, Betzig says.

The method is not suited to live imaging, he says, because it takes too long to switch the photoactivatable molecules on and off. What's more, the repeated light exposure damages cells and their fluorescent labels. "The problem with this approach is that you first turn on all the molecules, then you immediately turn off almost all the molecules. The molecules you've turned off don't contribute anything to the image, but you've just fried them twice. You're stressing the molecules, and it takes a lot of time, which you don't have, because the cell is moving."

The solution was simple, Betzig says: "Don't turn on all of the molecules. There's no need to do that." Instead, the new method, called patterned photoactivation non-linear SIM, begins by switching on just a subset of fluorescent labels in a sample with a pattern of light. "The patterning of that gives you some high resolution information already," he explains. A new pattern of light is used to deactivate molecules, and additional information is read out of their deactivation. The combined effect of those patterns leads to final images with 62-nanometer resolution--better than standard SIM and a three-fold improvement over the limits imposed by the wavelength of light.

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.

Topic world Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy has revolutionized life sciences, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. With its ability to visualize specific molecules and structures in cells and tissues through fluorescent markers, it offers unique insights at the molecular and cellular level. With its high sensitivity and resolution, fluorescence microscopy facilitates the understanding of complex biological processes and drives innovation in therapy and diagnostics.